Veterans are some of the most valuable cybersecurity talent we have

and that pipeline is going to dwindle more than it ever has

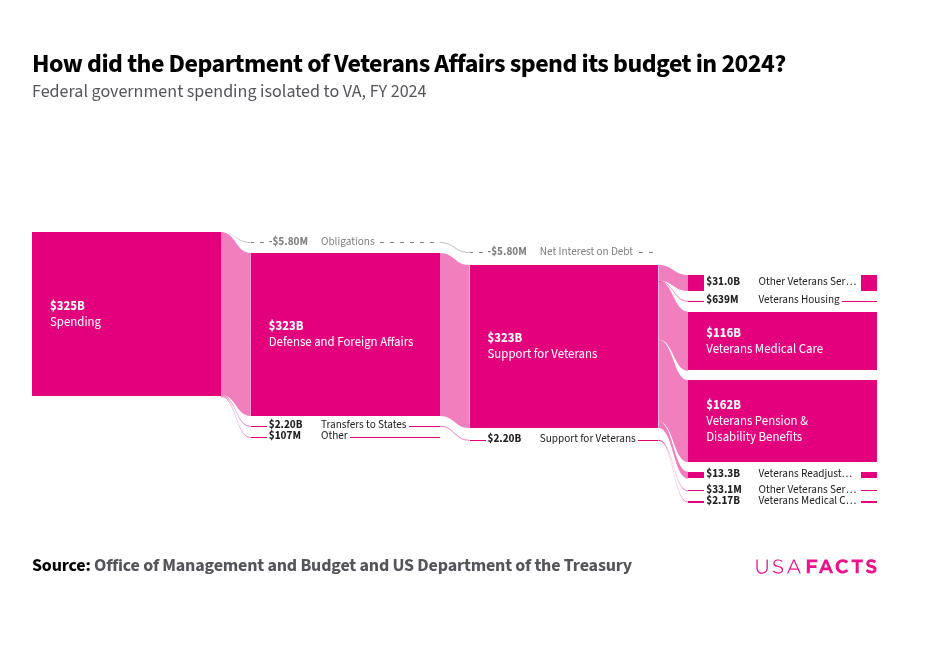

The Department of Veterans Affairs has three administrations: the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA), and the National Cemetery Administration (NCA). These administrations focus on a few main areas:

Veterans medical care: The Veterans Health Administration provides care to 9.1 million enrolled veterans, about half of the 18 million living veterans in the United States. It’s supported by over 410,000 VHA employees.

Veterans pension and disability benefits: As of 2022, 30% of US veterans had service-connected disabilities, or about 5.4 million, that receive some level of benefits. It’s supported by over 32,000 VBA employees.

Veterans housing: As of 2024, over 32,000 veterans were experiencing homelessness, which is a record low. The VA permanently housed 47,925 homeless veterans in 2024. It’s also supported by VBA employees.

Veterans national cemeteries: In 2025, the VA expects to provide the internment of over 137,000 veterans and eligible family members in VA national cemeteries. It’s supported by over 2,000 NCA employees.

The vast majority of employees in the VA are employed at the VHA, while the VBA employs under 10% and the NCA under 1%.

I never thought I’d reference a graphic from Steve Ballmer, but here we are.

The VA hovers between 2% - 5% of the overall federal budget and currently employs 482,000 people. For reference, veterans make up about 6% of the civilian population over the age of 18.

To sum up what the VA does in one sentence: it works to help provide dignity and support for United States veterans. Is it perfect at this? Absolutely not. However, it has improved overall health outcomes and veteran satisfaction significantly - in many cases better than the private sector - over the past 30 years.

What happened: Since February 13, the VA has laid off 2,400 employees in “non mission-critical positions” and probationary employees. Now, according to an internal memo, the VA plans to cut 80,000 jobs, likely starting in June. This will bring the number of employees at the department under 400,000. Given the concentration of staff at VHA, it’s likely that veteran healthcare will be affected by these cuts.

Take note: There’s two angles to this: the challenge to the cybersecurity posture of the VA and the threat to the cybersecurity workforce.

First, the challenge to the cybersecurity posture of the VA. Three factors are at play here:

In November, the VAs top IT official made clear that the VAs cybersecurity organization is understaffed. They currently have 360 information security officers, and at the time he stated the number of officers should almost double that at over 600. Not ideal with staff cuts coming, though hopefully it will not affect the cybersecurity division.

The lead for cybersecurity for VA.gov was let go as part of DOGE layoffs from US Digital Service. He also co-led a project (with another employee who resigned) to migrate the VA.gov site to the VA cloud environment, VA Enterprise Cloud, for security and performance reasons. Losing two key leads on a project like this is difficult to quickly recover from, and it’s unknown if the project will continue.

In 2022, the PACT act was signed into law, providing coverage for veterans exposed to toxic substances. Since then, there has been a surge in enrollment — between August 2022 and August 2024, there’s been a 33% increase in enrollment over the previous two-year period. Great news for veterans, but difficult timing for VA staff in the face of layoffs.

Removing shared services support from the United States Digital Service (Now DOGE) and potentially reducing an already understaffed workforce, plus a massive increase in enrollment in veteran services, will put strain on the cybersecurity organization at the VA. Given that the VA delayed the update to electronic health record deployments into 2026, and the cloud migration of the VA.gov site will likely be delayed, there are clearly multiple high priority tech advancements in flight that will not be completed soon. Legacy technology in the face of increased user demand inevitably spells a security risk.

Second, the threat to the cybersecurity workforce. In 2023, Forrester published data analyzing LinkedIn profiles of Fortune 500 CISOs, and in that data, found that 14% listed prior experience in the armed forces. The cybersecurity industry and veteran population are undeniably intertwined. Some of the most prominent cybersecurity experts are veterans: Lesley Carhart, Joe Slowik, Kevin Mandia, Robert M Lee, Chase Cunningham, Bryson Bort, Marcus Carey, Chris Cochran, Callie Guenther, to name just a few.

Many security companies have programs to employ veterans straight out of the military because they understand the value veterans bring to the cybersecurity workforce. Others provide training and job placement opportunities, like Splunk, Fortinet, Microsoft, Cisco, IBM, SANS…the list goes on.

The recognition of veteran’s importance to cybersecurity is not limited to the private sector: 39% of public sector cybersecurity new hires are veterans.

Veterans perform so effectively in cybersecurity roles because they understand the mission. They often have experience with some of the most prominent threat actors, and have a unique point of view on how governments approach warfare, whether the experience is in cybersecurity or not.

The problem is, we know that the majority of US military branches are not meeting their enlistment goals. Further, the veteran population dwindles every year.

The VA could act as a buffer here, both by providing quality service to aging veterans (more than 30% of the federal cyber workforce is over 55) and by supporting veterans transitioning to new roles. The VA does two very important things to support veterans moving on to other jobs like cybersecurity after military service: it provides healthcare and it provides benefits.

On healthcare, DOD’s Propensity Update data showed that in 2021, 2022, and 2023, the “possibility of PTSD or other emotional/psychological issues” is the second most cited reason not to serve. A strong VHA supports veterans through these challenges and can help manage health concerns like these. However, any program addressing emotional or psychological challenges requires trained staff.

On benefits, the second most cited reason to serve is “to pay for future education”. The VA administers the GI Bill and provides services like VET TEC, a program to provide eligible veterans with financial assistance on technical education training courses without relying on their GI Bill benefits. The administration of these services requires staff, especially to reduce wait times, and partnership development.

How veterans are treated post-service affects their willingness to join the military. But unfortunately, between DOGE contract cuts, employee layoffs, and increased veteran demand, care in both these areas will inevitably suffer. The math doesn’t work out any other way.

Be kind to the veterans you know and do your best to open up opportunities for the ones you don’t yet know.

I want to hear your perspective!

⬇️⬇️⬇️ Share a comment with me below. ⬇️⬇️⬇️