Attributing cyberattacks to a specific actor is harder than it looks

Patience is a virtue and can prevent an international incident

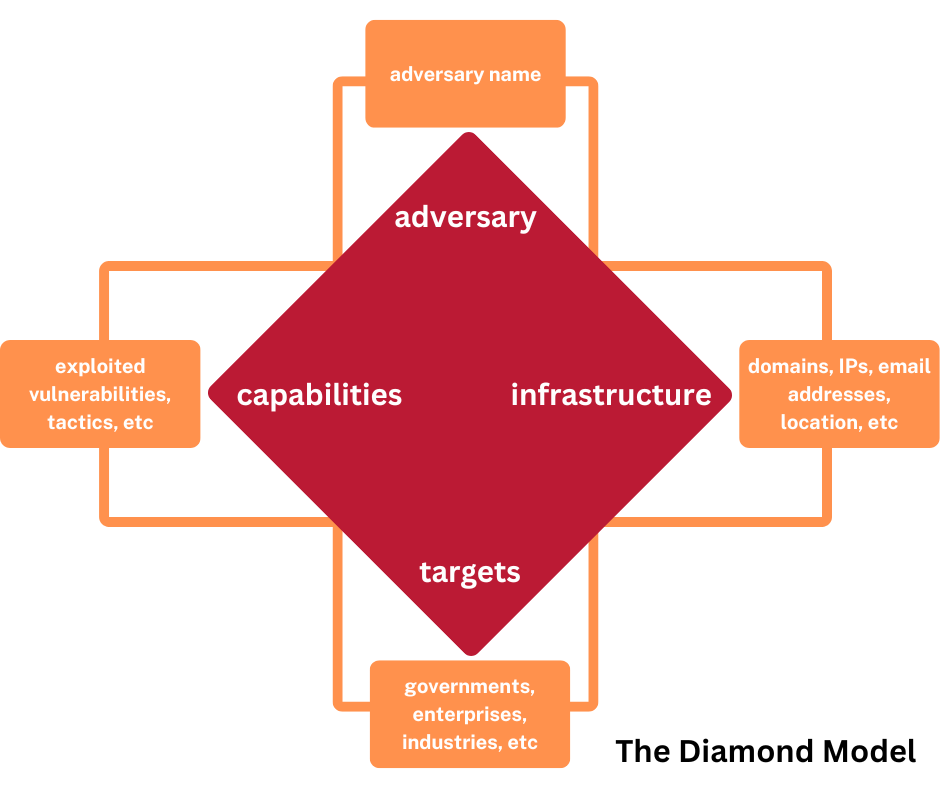

Cyberattacks leave a little trail of breadcrumbs in the form of IP addresses, domains, specific tactics, programming languages, email addresses, comments, specific vulnerabilities targeted, known objectives, malware signatures, and other information. Security practitioners use The Diamond Model to structure how they understand and relate attacker activity to potential known groups. If you know the infrastructure the attacker typically uses, what capabilities it uses to target that infrastructure, and what targets it attempts to break into, you can make an approximation of which attacker it is most likely to be.

The Diamond Model is predicated on two things:

Every attacker uses capabilities executed on infrastructure against targets.

Every attacker has a specific motivation and goal it wants to achieve.

While this makes attribution seems simple, it can become quite complicated.

The first complication in attribution: security researchers need to be accurate and timely with their attribution. To do attribution well, it requires the right resources - skilled security researchers and time — and the right data. It can be easy to misattribute attacker activity without a thorough view of the attack landscape on all domains: not just the devices we use every day, but also the cloud resources, networks, identities, and data.

Misattribution (and sometimes attribution!) can lead to heightened geopolitical tensions and the escalation of conflict. It wasn’t that long ago that one of the first and most groundbreaking attribution reports was released: Mandiant’s APT 1 Report in 2013. The report led to the first time the US indicted known state actors for hacking.

Attribution has consequences.

The second complication in attribution: attackers know just as well as cybersecurity professionals that it’s possible to track their activity. Nation-state attackers may attempt to hide their breadcrumbs to ensure attacks can’t be traced back to them or their nation. They do this in a few ways:

Obfuscating their IP address. Just because an IP address seems to originate in Brazil doesn’t mean it actually does! Attackers use jump boxes, intermediary devices, to pretend like they are in a different location. These devices can be legitimate systems that they are hijacking. Someone in Germany may connect to a jump box, then connect to their actual target. While they are still in Germany, it looks like they are in Brazil. Attackers can also use VPNs to do this - if the VPN is located in Brazil, the attacker will get a visible IP address in Brazil. In this scenario, you wouldn’t want to accuse Brazil!

Burning their domains, email addresses, or other common identifiers. Just like a spy getting a new burner phone for every new mission, attackers can change up the infrastructure they use to make sure certain attacks can’t be tied back to other attacks they have perpetrated. The breadcrumbs disappear into a dead end.

Changing their tactics. Nation state attackers often evolve their tradecraft and find new and innovative attack vectors, including new zero day vulnerabilities and exploits. Net new attacker activity can be difficult to attribute to a specific actor because of it.

Manufacturing a false flag operation. Just like how some criminals will try to plant evidence at a crime scene, nation state attackers will also. They plant evidence - documents, malware written in certain languages, different types of malware that is known to be associated with another nation state, to mislead people into suspecting another group.

Establishing a trickle-down effect with malware sharing. After the novelty of a new type of nation state malware wears off, the nation state actors may release the code to cybercriminal communities. Once the cybercriminals start using it, it becomes very difficult to tell if and when the malware is being used by a cybercriminal or a nation state, further obfuscating their activities.

It takes weeks at minimum to do attribution well, though in some instances it can take years of careful tracing and analysis.

What happened: Last week, the social media platform X was hit with a cyberattack that affected many of the features on the site. The attack, a distributed-denial-of-service attack (DDoS), is where attackers attempt to overload the website by sending it an overwhelming amount of traffic. It’s kind of like how we are bombarded with so much information on the Internet every day, we eventually have to take a break for our sanity. The website under a DDoS attack can do the same thing. The owner of X, Elon Musk, told media outlets that some IP addresses associated with the attack originated in Ukraine. Given Musk’s proximity to the White House and the divisive state of peace talks between the US, Russia, and Ukraine, the Internet exploded with speculation. After all was said and done, a pro-Palestinian group called Dark Storm took responsibility for the attack.

Take note: As we discussed above, having some IP addresses originate in Ukraine does not mean an attack was started by Ukrainians. It’s even more difficult to attribute a DDoS attack, as very often the traffic will come from multiple different locations in what’s known as a botnet. Attackers access a bunch of hijacked devices, which can be anywhere in the world, and have them direct traffic to a specific website. They have to do this inherently — how else would they get enough traffic to take down a website?

The ultimate lesson here: if attribution happens before a cyberattack is over, or even in the same day, it is definitely uninformed and is most likely wrong. Always look for an in-depth analysis, multiple indicators that point to a specific nation state (across each point of the Diamond Model), and a team that has a broad view of activity by all nation states, cybercriminal groups, and hacktivists (typically a big cybersecurity vendor will be supporting the company in their retrospective).